There are nights when words feel useless, and yet a single poem finds its way through the dark. Poems about grief are like that. They arrive quietly, carrying the ache of others, and in that shared language, something begins to loosen.

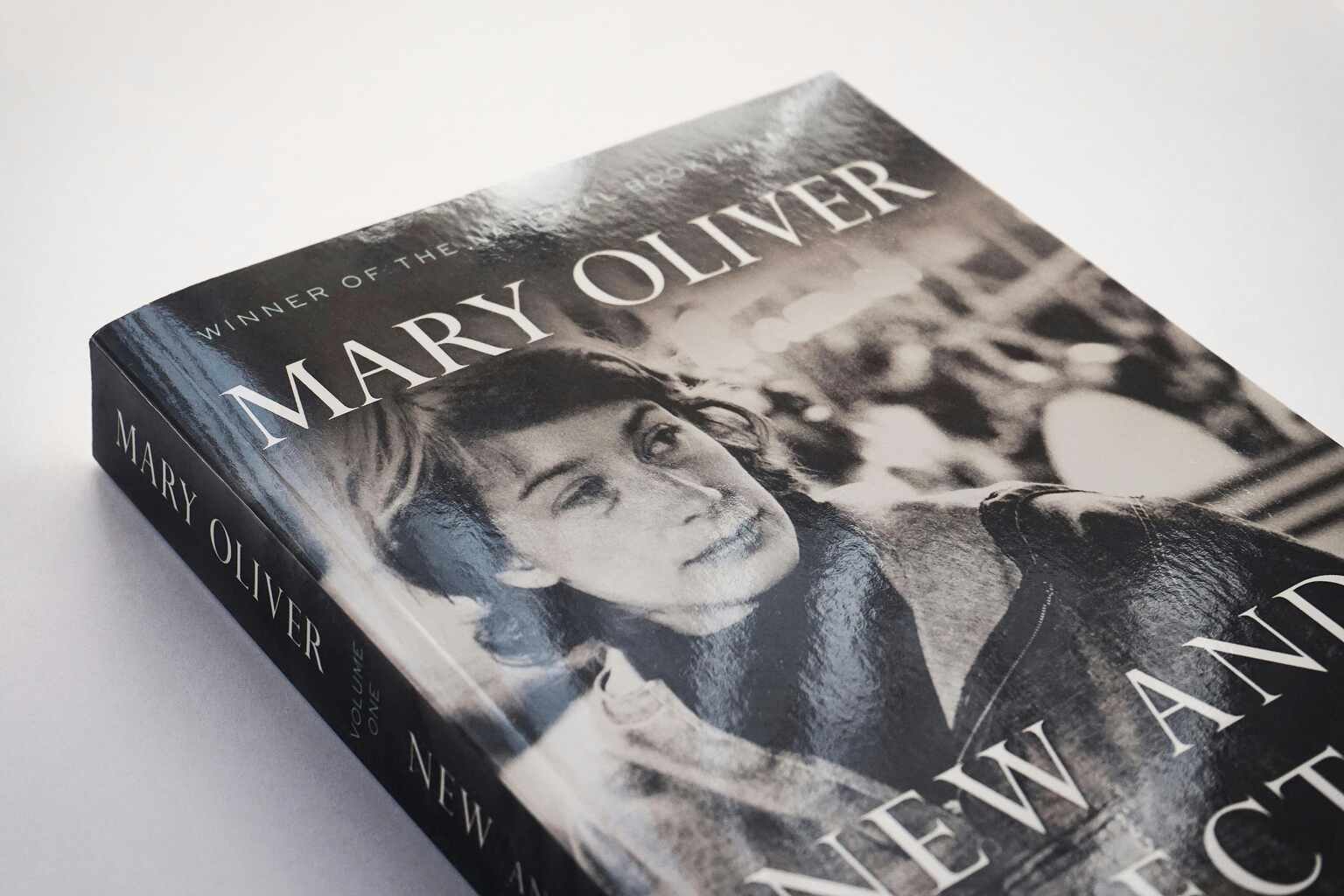

Through history, grief has made poets its witnesses. Dickinson, Auden, Oliver, Vuong – each found a different voice for pain, but the need was the same. To name absence, to remember, to keep love alive in another form. This is how grief poetry survives time. It listens when nothing else does.

Here you will find poems about grief and loss that speak to the living. Some reach back to old elegies; others belong to a more fractured, modern heart. Together they hold a truth that cannot be hurried: when you are losing someone you love, the words that heal will not rush you. They will simply stay.

Grief Poems And Their History

In the beginning, grief was not written but spoken. The first poems about death belonged to the living who could not stay silent. They were sung beside water, or whispered into the soil, because language felt sacred when loss was near. Later, poets like Milton turned that voice into form, shaping pain through rhythm and restraint. Rossetti followed with a gentler devotion, her verses tender and reverent toward the loss of a loved one.

When mourning became private, modern poets arrived with simpler words. Mary Oliver’s lines breathe like prayer without religion. Ocean Vuong writes grief as confession, his voice unraveling softly through memory. In them, the old grandeur of mourning becomes something personal. The audience is no longer the crowd, but the self.

Across centuries, poems about grief and loss have changed their sound but not their purpose. Each sympathy poem still carries its small offering of sadness and love, asking the same unanswerable question: how do we live with absence? The words cannot solve it, but they can remember. And remembering is all poetry has ever promised. From public elegy to private lyric, the current of death poetry has kept the same human need at its core.

Can Grief Poems Help With Healing?

Poetry cannot erase grief; it only teaches the hands how to hold it. When the world feels too quiet, poems about grief speak softly back. Their rhythm steadies breath, reminding the heart it is still capable of movement. The rhythm steadies what chaos leaves behind.

Writing, too, becomes a form of release. Studies on expressive writing show that putting loss into language can ease emotional distress and support healing through grief. The University of Central Lancashire’s Poetry and Loss project found that reading and creating poems helps mourners shape meaning from pain, a quiet reordering of what feels unendurable.

Certain poems will make you cry, but even those tears carry clarity. The repetition, the careful return of a word, soothes the nervous system as much as the soul. Poetry does not cure absence; it teaches endurance. As Maria Popova once wrote, grief is “the shadow love casts in the light of loss,” and poetry allows that shadow to be seen, not feared.

The collection that follows is meant for that space between silence and survival. Each piece is both touching and emotionally powerful, written by someone who once stood where you are standing. These poems do not promise closure; they simply promise company.

15 Poems About Grief And Loss To Help You Heal

The poems that follow move through every color of absence. Some mourn, some remember, some forgive. Read them as one long breath of grief poetry, a chorus of poems about grief and loss that understand what it means to keep losing someone you love and still remain.

1. “Funeral Blues” — by W.H. Auden

Auden’s Funeral Blues begins with the impossible request to halt the world. In those lines, every mourner finds recognition. Once playful, it grew into an elegy of raw truth, a voice for anyone losing someone you love. Among poems about grief and loss, it is the most painfully direct.

It will make you cry not for beauty, but for honesty. Each image carries stillness, the kind that grief leaves behind. It is often called the saddest poem ever written, a phrase readers still use when they cannot find any other way to say how utterly it breaks the world.

Funeral Blues

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message ‘He is Dead’.

Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

2. “Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep” — by Mary Elizabeth Frye

This poem speaks softly, the way comfort does when words are scarce. It asks you not to weep but to look toward what still moves. The spirit, Frye writes, becomes light, wind, and quiet earth. Anonymous in origin, it has long guided mourners through the loss of a loved one. Few poems about death hold such calm certainty. Its message is not escape but transformation, a reminder that healing through grief can begin with noticing the world again. Among sympathy poems, it endures for its simplicity, offering reassurance without promise, and love without end.

Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep by Mary Elizabeth Frye

Do not stand at my grave and weep

I am not there. I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow.

I am the diamond glints on snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain.

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry;

I am not there. I did not die.

3. “Heavy” — by Mary Oliver

Heavy is a quiet conversation between the heart and what it cannot undo. Oliver’s words hold sadness the way one holds light, carefully, so it doesn’t slip away. This is grief poetry written with compassion, turning despair into understanding. She writes as if grief were a companion that teaches, not a wound that punishes. It is deeply emotionally powerful because it forgives the weight itself. Healing through grief here means learning to coexist with what remains, to carry love inside loss without asking it to leave. Few poems describe that balance so gently, or so well.

Heavy

That time

I thought I could not

go any closer to grief

without dying

I went closer,

and I did not die.

Surely God

had his hand in this,

as well as friends.

Still, I was bent,

and my laughter,

as the poet said,

was nowhere to be found.

Then said my friend Daniel,

(brave even among lions),

“It’s not the weight you carry

but how you carry it–

books, bricks, grief–

it’s all in the way

you embrace it, balance it, carry it

when you cannot, and would not,

put it down.”

So I went practicing.

Have you noticed?

Have you heard

the laughter

that comes, now and again,

out of my startled mouth?

How I linger

to admire, admire, admire

the things of this world

that are kind, and maybe

also troubled –

roses in the wind,

the sea geese on the steep waves,

a love

to which there is no reply?

4. “Nothing Gold Can Stay” — by Robert Frost

Nothing Gold Can Stay reads like a moment suspended between breath and silence. Frost writes of change with such calm that it hurts. Among short poems about grief and love, few say so much with so little. The poem feels like a goodbye spoken softly to beauty itself. Its sadness lies not in death but in passing, in how even joy cannot remain untouched. This is grief poetry that understands impermanence without bitterness, where every fading thing leaves a trace of light. In its brevity, Frost reveals how loss is always near, gentle but inevitable.

Nothing Gold Can Stay

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

5. “Dirge Without Music” — by Edna St. Vincent Millay

There is no comfort here, only truth. Millay writes Dirge Without Music as a protest, not a prayer. In a world full of poems about grief that whisper, she dares to shout. Her words resist the softness of ceremony, facing death with fury instead of reverence. That honesty made it one of the most famous grieving poems in modern memory. The poem’s sadness feels alive, burning rather than weeping. It captures that moment when acceptance seems impossible, when mourning becomes defiance. Few poems about death carry such human weight, demanding that grief be felt, not hidden.

Dirge Without Music

I am not resigned to the shutting away of loving hearts in the hard ground.

So it is, and so it will be, for so it has been, time out of mind:

Into the darkness they go, the wise and the lovely. Crowned

With lilies and with laurel they go; but I am not resigned.

Lovers and thinkers, into the earth with you.

Be one with the dull, the indiscriminate dust.

A fragment of what you felt, of what you knew,

A formula, a phrase remains,—but the best is lost.

The answers quick and keen, the honest look, the laughter, the love,—

They are gone. They are gone to feed the roses. Elegant and curled

Is the blossom. Fragrant is the blossom. I know. But I do not approve.

More precious was the light in your eyes than all the roses in the world.

Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave

Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave.

I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

RELATED READING: 9 Best Poems By Emily Dickinson: Beauty, Love, And Death

6. “Tonight I Can Write (The Saddest Lines)” — by Pablo Neruda

This poem exists where love and mourning meet. Neruda writes of loss with the intimacy of someone still listening for an echo. Within grief poetry, few voices sound so personal, so unbearably human. The saddest line of Pablo Neruda—“Love is so short, forgetting is so long” – captures that endless ache of losing someone you love. It is emotionally touching because it tells the truth without ornament. The night, the stars, the silence, all become part of the same grief. Here, sorrow is not dramatic; it is patient, slow, and deeply alive.

Tonight I Can Write (The Saddest Lines)

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

Write, for example, ‘The night is starry and the stars are blue and shiver in the distance.’

The night wind revolves in the sky and sings.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too.

Through nights like this one I held her in my arms.

I kissed her again and again under the endless sky.

She loved me, sometimes I loved her too.

How could one not have loved her great still eyes.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

To think that I do not have her. To feel that I have lost her.

To hear the immense night, still more immense without her.

And the verse falls to the soul like dew to the pasture.

What does it matter that my love could not keep her.

The night is starry and she is not with me.

This is all. In the distance someone is singing. In the distance.

My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

My sight tries to find her as though to bring her closer.

My heart looks for her, and she is not with me.

The same night whitening the same trees.

We, of that time, are no longer the same.

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but how I loved her.

My voice tried to find the wind to touch her hearing.

Another’s. She will be another’s. As she was before my kisses.

Her voice, her bright body. Her infinite eyes.

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but maybe I love her.

Love is so short, forgetting is so long.

Because through nights like this one I held her in my arms

my soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

Though this be the last pain that she makes me suffer

and these the last verses that I write for her.

Translation by W. S. Merwin

7. “Talking to Grief” — by Denise Levertov

Levertov’s Talking to Grief feels like an offering, a moment of quiet surrender. She does not fight her sorrow; she sits with it. This poem redefines mourning as companionship, the heart learning to share its room. It stands among poems about grief and loss that are most emotionally powerful because they do not reach for relief. Instead, this grief poetry shows how healing through grief comes from allowing what hurts to exist without shame. Levertov’s words hold grief the way one might hold a fragile bird, careful not to let it escape before it learns to rest.

Talking To Grief

Ah, Grief, I should not treat you

like a homeless dog

who comes to the back door

for a crust, for a meatless bone.

I should trust you.

I should coax you

into the house and give you

your own corner,

a worn mat to lie on,

your own water dish.

You think I don’t know you’ve been living

under my porch.

You long for your real place to be readied

before winter comes. You need

your name,

your collar and tag. You need

the right to warn off intruders,

to consider

my house your own

and me your person

and yourself

my own dog.

8. “Remember” — by Christina Rossetti

In Remember, Rossetti offers a parting that feels like prayer. Her voice is calm, never pleading, accepting that memory will fade as life continues. Among poems about loss of a loved one, few speak with such restraint. It belongs to the long tradition of sympathy poems that comfort by letting go. The poem holds both sadness and love in equal measure, refusing to turn grief into guilt. Rossetti’s tenderness lies in permission, the invitation to live fully even after farewell. To remember becomes enough, a quiet act of keeping what was once everything.

Remember

Remember me when I am gone away,

Gone far away into the silent land;

When you can no more hold me by the hand,

Nor I half turn to go yet turning stay.

Remember me when no more day by day

You tell me of our future that you plann’d:

Only remember me; you understand

It will be late to counsel then or pray.

Yet if you should forget me for a while

And afterwards remember, do not grieve:

For if the darkness and corruption leave

A vestige of the thoughts that once I had,

Better by far you should forget and smile

Than that you should remember and be sad.

9. “On Love” — by Kahlil Gibran

On Love speaks in the language of surrender. Gibran reminds us that whoever opens the heart must also accept the ache it invites. Few poems about grief hold this balance so tenderly. His vision is emotionally powerful because it sees no separation between joy and pain, only rhythm. In that rhythm, healing through grief becomes natural, not forced. He writes that love cuts and comforts with the same hand, that to love is to be carved into wholeness. Through such clarity, love becomes not the opposite of sorrow but its reason for staying.

On Love

Then said Almitra, Speak to us of Love.

And he raised his head and looked upon the people, and there fell a stillness upon them. And with a great voice he said:

When love beckons to you, follow him,

Though his ways are hard and steep.

And when his wings enfold you yield to him,

Though the sword hidden among his pinions may wound you.

And when he speaks to you believe in him,

Though his voice may shatter your dreams as the north wind lays waste the garden.

For even as love crowns you so shall he crucify you. Even as he is for your growth so is he for your pruning.

Even as he ascends to your height and caresses your tenderest branches that quiver in the sun,

So shall he descend to your roots and shake them in their clinging to the earth.

Like sheaves of corn he gathers you unto himself

He threshes you to make your naked.

He sifts you to free you from your husks.

He grinds you to whiteness.

He kneads you until you are pliant;

And then he assigns you to his sacred fire, that you may become sacred bread for God’s sacred feast.

All these things shall love do unto you that you may know the secrets of your heart, and in that knowledge become a fragment of Life’s heart.

But if in your heart you would seek only love’s peace and love’s pleasure,

Then it is better for you that you cover your nakedness and pass out of love’s threshing-floor,

Into the seasonless world where you shall laugh, but not all of your laughter, and weep, but not all of your tears.

Love gives naught but itself and takes naught but from itself.

Love possesses not nor would it be possessed;

For love is sufficient unto love.

When you love you should not say, “God is in my heart,” but rather, “I am in the heart of God.”

And think not you can direct the course of love, for love, if it finds you worthy, directs your course.

Love has no other desire but to fulfil itself.

But if you love and must needs have desires, let these be your desires:

To melt and be like a running brook that sings its melody to the night.

To know the pain of too much tenderness.

To be wounded by your own understanding of love;

And to bleed willingly and joyfully.

To wake at dawn with a winged heart and give thanks for another day of loving;

To rest at the noon hour and meditate love’s ecstasy;

To return home at eventide with gratitude;

And then to sleep with a prayer for the beloved in your heart and a song of praise upon your lips.

10. “Time Does Not Bring Relief” — by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Millay’s Time Does Not Bring Relief rejects the comfortable lie that sorrow fades. Among poems about death, few sound so certain, so unwilling to forget. The poem moves through memory like weather that never changes, naming the ache that lingers where love once lived. It belongs to the most enduring grief poetry, emotionally touching in its refusal to soften. Millay’s honesty is its beauty; she tells the truth that time only teaches us how to live beside sadness, not without it. For those who need truth more than comfort, her words feel like steady ground.

“Time does not bring relief; you all have lied”

Time does not bring relief; you all have lied

Who told me time would ease me of my pain!

I miss him in the weeping of the rain;

I want him at the shrinking of the tide;

The old snows melt from every mountain-side,

And last year’s leaves are smoke in every lane;

But last year’s bitter loving must remain

Heaped on my heart, and my old thoughts abide.

There are a hundred places where I fear

To go,—so with his memory they brim.

And entering with relief some quiet place

Where never fell his foot or shone his face

I say, “There is no memory of him here!”

And so stand stricken, so remembering him.

RELATED READING: 7 Poems That Prove E.E. Cummings Is The Only Poet You’ll Ever Need To Read

11. “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong” — by Ocean Vuong

In Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong, the poet writes to his own reflection, tenderly repairing what grief once fractured. The poem bends sadness into song, finding beauty in survival. It belongs to the newer lineage of poems about grief and love that turn mourning inward. Vuong’s grieving poems linger because they do not separate loss from identity. They remind us that to live is to keep translating pain into meaning. The work feels emotionally powerful not through grand gesture but through vulnerability, as if forgiveness were an act of remembering who you have always been.

Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong

Ocean, don’t be afraid.

The end of the road is so far ahead

it is already behind us.

Don’t worry. Your father is only your father

until one of you forgets. Like how the spine

won’t remember its wings

no matter how many times our knees

kiss the pavement. Ocean,

are you listening? The most beautiful part

of your body is wherever

your mother’s shadow falls.

Here’s the house with childhood

whittled down to a single red trip wire.

Don’t worry. Just call it horizon

& you’ll never reach it.

Here’s today. Jump. I promise it’s not

a lifeboat. Here’s the man

whose arms are wide enough to gather

your leaving. & here the moment,

just after the lights go out, when you can still see

the faint torch between his legs.

How you use it again & again

to find your own hands.

You asked for a second chance

& are given a mouth to empty out of.

Don’t be afraid, the gunfire

is only the sound of people

trying to live a little longer

& failing. Ocean. Ocean —

get up. The most beautiful part of your body

is where it’s headed. & remember,

loneliness is still time spent

with the world. Here’s

the room with everyone in it.

Your dead friends passing

through you like wind

through a wind chime. Here’s a desk

with the gimp leg & a brick

to make it last. Yes, here’s a room

so warm & blood-close,

I swear, you will wake —

& mistake these walls

for skin.

12. “One Art” — by Elizabeth Bishop

In One Art, Bishop turns the language of loss into discipline. The poem begins with small misplacements, then moves toward heartbreak so gently you almost miss the breaking. Among short poems about grief and love, it is the most composed, the most wounded. Its calm tone hides sadness so complete it becomes art itself. This grief poetry does not seek comfort; it demonstrates endurance, the kind that lives behind steady hands. The final line falters on purpose, proving that loss can never be fully rehearsed, only written again and again until it feels almost ordinary.

For readers mourning the loss of mother, Bishop’s quiet escalation carries that particular, private ache with a clarity that both steadies and breaks the heart.

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

13. “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” — by Emily Dickinson

Because I Could Not Stop for Death reads like a conversation between equals. Dickinson personifies Death as patient, almost kind, and in doing so, disarms him. Among poems about death, few are so famous or so restrained. This is grief poetry turned philosophical, serene in its inquiry. The carriage moves without haste, past the stages of life toward quiet eternity. What lingers is not fear but wonder—the recognition that mortality is part of the same design as love and time. Dickinson’s vision makes the inevitable feel almost divine, soft as dusk.

Because I could not stop for Death – (479)

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer, my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

14. “Death Is Nothing at All” — by Henry Scott-Holland

Death Is Nothing at All carries the tone of a hand resting softly on grief and growth. Scott-Holland speaks as though from the threshold, assuring that love remains untouched. Among poems about loss of a loved one, this one comforts through understatement. It has become one of the most enduring sympathy poems, recited where hearts need calm. Its vision of healing through grief is simple: remember the person as they were, still near, still part of the ordinary. The poem’s peace lies in its acceptance, its gentle insistence that love’s language does not end with silence.

Death Is Nothing At All

Death is nothing at all.

I have only slipped away to the next room.

I am I and you are you.

Whatever we were to each other,

That, we still are.

Call me by my old familiar name.

Speak to me in the easy way

which you always used.

Put no difference into your tone.

Wear no forced air of solemnity or sorrow.

Laugh as we always laughed

at the little jokes we enjoyed together.

Play, smile, think of me. Pray for me.

Let my name be ever the household word

that it always was.

Let it be spoken without effect.

Without the trace of a shadow on it.

Life means all that it ever meant.

It is the same that it ever was.

There is absolute unbroken continuity.

Why should I be out of mind

because I am out of sight?

I am but waiting for you.

For an interval.

Somewhere. Very near.

Just around the corner.

All is well.

15. “The Tenth Elegy” — by Rainer Maria Rilke

Rilke’s The Tenth Elegy closes his great work with stillness, turning despair into understanding. It is both prayer and acceptance, one of those poems about grief and loss that refuse to end in darkness. Within its vast calm, beauty and pain coexist, bound by faith in transformation. As grief poetry, it is less about lament than awakening, where sorrow reveals the sacred within ordinary life. Among poems about death, few feel so luminous. Rilke teaches that sadness is not absence but evidence of how deeply we have lived, how love makes even endings shine.

The Tenth Elegy

That some day, emerging at last from the terrifying vision

I may burst into jubilant praise to assenting angels!

That of the clear-struck keys of the heart not one may fail

to sound because of a loose, doubtful or broken string!

That my streaming countenance may make me more resplendent

That my humble weeping change into blossoms.

Oh, how will you then, nights of suffering, be remembered

with love. Why did I not kneel more fervently, disconsolate

sisters, more bendingly kneel to receive you, more loosely

surrender myself to your loosened hair? We, squanderers of

gazing beyond them to judge the end of their duration.

They are only our winter’s foliage, our sombre evergreen,

one of the seasons of our interior year, -not only season,

but place, settlement, camp, soil and dwelling.

How woeful, strange, are the alleys of the City of Pain,

where in the false silence created from too much noise,

a thing cast out from the mold of emptiness

swaggers that gilded hubbub, the bursting memorial.

Oh, how completely an angel would stamp out their market

of solace, bounded by the church, bought ready for use:

as clean, disappointing and closed as a post office on Sunday.

Farther out, though, there are always the rippling edges

of the fair. Seasaws of freedom! High-divers and jugglers of zeal!

And the shooting-gallery’s targets of bedizened happiness:

targets tumbling in tinny contortions whenever some better

marksman happens to hit one. From cheers to chance he goes

staggering on, as booths that can please the most curious tastes

are drumming and bawling. For adults ony there is something

special to see: how money multiplies. Anatomy made amusing!

Money’s organs on view! Nothing concealed! Instructive,

and guaranteed to increase fertility!…

Oh, and then outside,

behind the farthest billboard, pasted with posters for ‘Deathless,’

that bitter beer tasting quite sweet to drinkers,

if they chew fresh diversions with it..

Behind the billboard, just in back of it, life is real.

Children play, and lovers hold each other, -aside,

earnestly, in the trampled grass, and dogs respond to nature.

The youth continues onward; perhaps he is in love with

a young Lament….he follows her into the meadows.

She says: the way is long. We live out there….

Where? And the youth

follows. He is touched by her gentle bearing. The shoulders,

the neck, -perhaps she is of noble ancestry?

Yet he leaves her, turns around, looks back and waves…

What could come of it? She is a Lament.

Only those who died young, in their first state of

timeless serenity, while they are being weaned,

follow her lovingly. She waits for girls

and befriends them. Gently she shows them

what she is wearing. Pearls of grief

and the fine-spun veils of patience.-

With youths she walks in silence.

But there, where they live, in the valley,

an elderly Lament responds to the youth as he asks:-

We were once, she says, a great race, we Laments.

Our fathers worked the mines up there in the mountains;

sometimes among men you will find a piece of polished

primeval pain, or a petrified slag from an ancient volcano.

Yes, that came from there. Once we were rich.-

And she leads him gently through the vast landscape

of Lamentation, shows him the columns of temples,

the ruins of strongholds from which long ago

the princes of Lament wisely governed the country.

Shows him the tall trees of tears,

the fields of flowering sadness,

(the living know them only as softest foliage);

show him the beasts of mourning, grazing-

and sometimes a startled bird, flying straight through

their field of vision, far away traces the image of its

solitary cry.-

At evening she leads him to the graves of elders

of the race of Lamentation, the sybils and prophets.

With night approaching, they move more softly,

and soon there looms ahead, bathed in moonlight,

the sepulcher, that all-guarding ancient stone,

Twin-brother to that on the Nile, the lofty Sphinx-:

the silent chamber’s countenance.

They marvel at the regal head that has, forever silent,

laid the features of manking upon the scales of the stars.

His sight, still blinded by his early death,

cannot grasp it. But the Sphinx’s gaze

frightens an owl from the rim of the double-crown.

The bird, with slow down-strokes, brushes

along the cheek, that with the roundest curve,

and faintly inscribes on the new death-born hearing,

as though on the double page of an opened book,

the indescribable outline.

And higher up, the stars. New ones. Stars

of the land of pain. Slowly she names them:

“There, look: the Rider ,the Staff,and that

crowded constellation they call the the Garland of Fruit.

Then farther up toward the Pole:

Cradle, Way, the Burning Book, Doll, Window.

And in the Southern sky, pure as lines

on the palm of a blessed hand, the clear sparkling M,

standing for Mothers…..”

Yet the dead youth must go on alone.

In silence the elder Lament brings him

as far as the gorge where it shimmers in the moonlight:

The Foutainhead of Joy. With reverance she names it,

saying: “In the world of mankind it is a life-bearing stream.”

They reach the foothills of the mountain,

and there she embraces him, weeping.

Alone, he climbs the mountains of primeval pain.

Not even his footsteps ring from this soundless fate.

But were these timeless dead to awaken an image for us,

see, they might be pointing to th catkins, hanging

from the leafless hazels, or else they might mean

the rain that falls upon the dark earth in early Spring.

And we, who always think

of happiness as rising feel the emotion

that almost overwhelms us

whenever a happy thing falls.

Conclusion

Grief remains, though its voice grows tender with time. Poetry has always known this truth. Each poem, each small act of language, is a bridge between what was and what remains. Through grief poetry, the heart rediscovers its rhythm, learning that healing through grief means making beauty from ache.

These verses hold the fragments of remembrance, reshaped into light. They ask for nothing except that we keep listening. For anyone losing someone they love, may these words offer solace, the gentle kind that stays, long after the reading ends.

10 Genuine Websites To Download Books for Free – Updated 2026