I stumbled onto Camus by accident, opening The Stranger and being seized at once by its first line: “Maman died today. Or yesterday maybe, I don’t know.” It felt brutally cold, yet strangely liberating. I read on, and soon after I found my way to Sartre, who had lived and written beside Camus in the same cafés and circles of Paris. His Nausea shook me to the core. I began questioning not just ideas but ordinary objects, like a spoon left in the sink. That was when I realised the Camus vs Sartre relationship was really a struggle over how to be free, fought both on the page and in the politics of their time.

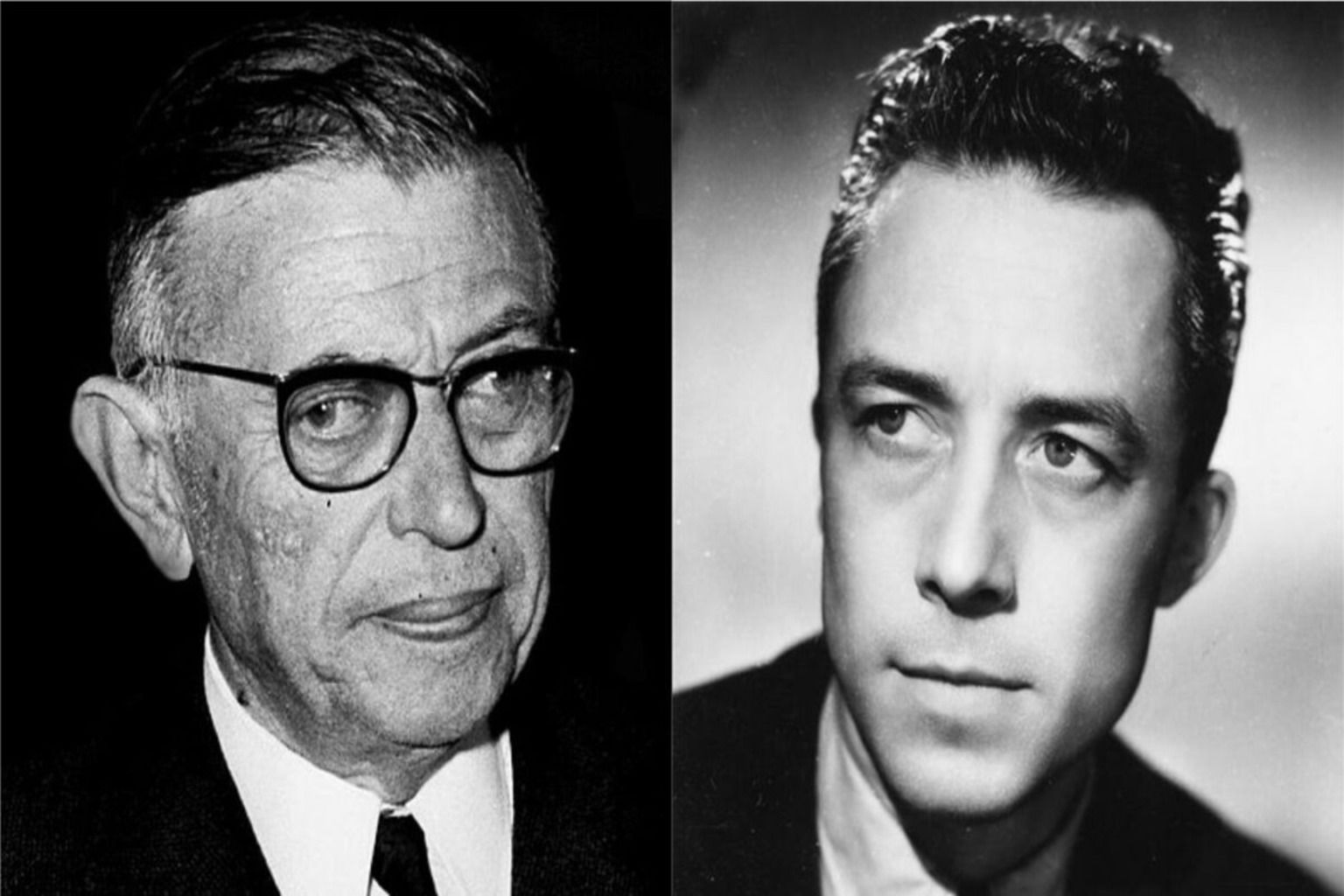

Albert Camus had the looks of a movie star and the background of a laborer’s son. Jean-Paul Sartre, small, sharp, and relentless, belonged to the Parisian intellectual class. They came together during the Occupation, when Paris was subdued and watchful, and stayed close as liberation arrived.

Camus and Sartre became public figures almost overnight. Camus’s essays in Combat urged France to think about dignity and responsibility. Sartre’s plays and lectures made him a household name. Newspapers reported where they drank coffee, what they read, and who they saw. They were treated less like scholars and more like guides to a continent in search of meaning.

The Camus vs Sartre relationship was forged in those years of hope, yet it carried tensions that soon surfaced. Camus distrusted systems that excused violence; Sartre argued justice demanded radical change. Their eventual break became headline news, a reflection of the divisions tearing through postwar politics.

Camus And Sartre – A Friendship Forged In Postwar Paris

The city they entered was marked by silence and control. Cafés dimmed their lights, newspapers carried only approved lines, and neighbors measured their words carefully. Camus, just beginning to find his audience through journalism and fiction, was drawn to Sartre’s intensity. Sartre, already known for his plays and essays, found in Camus a writer whose background gave him credibility outside the salons. They remained close once the war ended, speaking for a generation that wanted more than survival.

The Camus and Sartre relationship quickly became public property. Sartre planted himself at Les Deux Magots, a café that turned into an open office. Camus moved differently. He edited Combat, attended rehearsals, argued with editors, and appeared in unexpected corners of the city. Where Sartre was fixed, Camus was mobile, and together they gave the impression of a partnership always present and visible.

Their influence went beyond style. Readers looked to them for direction in answering questions no government could settle:

- What did freedom mean after dictatorship?

- Could Europe trust politics again, or only personal responsibility?

- Was philosophy enough to guide a society scarred by violence?

The Camus vs Sartre freedom debate had not yet emerged. In those first years, they shared common ground, giving existentialism its shape in postwar culture. The friendship carried weight not because they always agreed, but because their presence made philosophy feel urgent and alive.

RELATED READING: Love As Moral Transformation With Iris Murdoch: The Unselfing of Eros, And The Act Of Letting Go

The Shared Ground – Existentialism And The Search For Meaning

Existentialism offered Camus and Sartre a foundation they could share, which began with recognition of absurdity, mismatch between humanity’s search for meaning, and a universe that offered none. From this came two claims:

- People must create their values

- Freedom was unavoidable, yet freedom was not simple

In this framework, both men rejected religion. They believed it supplied false comfort rather than genuine direction. Instead, the demand was authenticity: to live as if choices carried real weight because they did. The result was a philosophy that spoke directly to a postwar public. It told readers that their lives, however ordinary, mattered because meaning was theirs to make.

The Camus philosophy of freedom is evident in his insistence that limits and responsibility define genuine liberty. Sartre agreed on the essentials. He wrote that humans are “condemned to be free,” forced to act without excuses, even when no higher authority guarantees the outcome. In these years, their accounts of freedom seemed to move in parallel, reinforcing one another rather than clashing.

Simone de Beauvoir remembered that her generation carried the burden of offering direction in a fractured world. For a time, Camus and Sartre met that need together. The Camus vs Sartre freedom debate had not yet surfaced, and their writings were heard almost as one voice. Existentialism spoke less like a theory and more like the condition of daily life, giving ordinary readers a sense that philosophy could mirror their uncertainties.

Camus’s Philosophy Of Revolt – Freedom With Limits

When Camus published The Rebel in 1951, he offered a philosophy of revolt that was both moral and political. The book argued that revolt begins when a person says “no” to injustice, but that refusal must never harden into absolute claims. To insist on total freedom or perfect justice was, in his view, to destroy both.

Camus wrote plainly: “Absolute freedom is the right of the strongest to dominate.” He added, “Absolute justice is achieved by the suppression of all contradiction: therefore, it destroys freedom.” These warnings captured the Camus philosophy of freedom. He believed genuine liberty could only survive when tempered by moderation, when people accepted limits as the condition for preserving human dignity.

What did this mean for politics? It meant that violence could not be justified as a normal instrument of change. Camus had accepted it under occupation, but in peacetime, he believed revolutionary violence corrupted the very ideals it claimed to defend. The real problem of how to be free was not solved by seizing power but by protecting space for human life against the lure of absolutes.

This was where the Camus-Sartre political philosophy divide opened. Sartre thought history demanded radical action; Camus believed history demanded humility. Sartre sided with revolution, Camus with restraint. Their readers understood that the argument was not academic. It reflected choices that faced postwar Europe, choices between competing visions of freedom itself.

RELATED READING: How To Be An Epicurean And Indulge In The Pleasures Of Life

Sartre’s Marxist Turn – Freedom Through Perfect Justice

Sartre’s reputation was built on existentialism, but by the early 1950s, his attention had shifted. He believed philosophy had to serve politics, and politics, in his view, required Marxism. Freedom, he argued, was impossible without justice. The worker at the factory floor was not free, no matter how much existential theory claimed otherwise. Freedom demanded equality first.

Sartre had once written, “We are left alone, without excuse.” In those words, he captured the essence of individual responsibility. But by the 1950s, he argued that such responsibility was meaningless in a system that denied people the material conditions of choice. Communism promised to eliminate want and to give each person a genuine opportunity. In practice, this meant endorsing revolutionary action. Sartre did not shy away from that implication. For him, violence was sometimes the cost of dismantling oppressive structures.

The paradox of Sartre Marxism freedom was clear. A philosophy that began with radical personal responsibility now pointed toward systems that curtailed it. Sartre believed history had its demands and that individuals must align with them. Camus saw this as dangerous absolutism.

The Camus Sartre political philosophy break grew from this dispute. Camus argued for moderation; Sartre demanded total commitment. For Sartre, neutrality was complicity, and hesitation was betrayal. For Camus, revolution betrayed humanity when it excused cruelty in the name of ideals. Their disagreement mirrored broader divisions across Europe, where communism gained followers but also revealed its authoritarian costs.

The Camus vs Sartre split revealed more than intellectual rivalry. It exposed a fundamental choice about freedom’s meaning. Should freedom be bound by limits to protect dignity, or pursued through equality even if it requires upheaval? Sartre’s position gave priority to justice, at times cutting into liberty. Camus’s position gave priority to liberty, even when justice remained unfinished.

Why Camus And Sartre Parted Ways

By 1951, the tension had become open conflict. Camus’s The Rebel argued that freedom must live within limits and condemned violence carried out in the name of history. It was an appeal for moderation in an age of extremes. Sartre and his allies read it as surrender.

Les Temps Modernes, Sartre’s journal, became the battlefield. In his review, Francis Jeanson painted Camus as naïve, blind to the hard truths of oppression. Camus wrote back angrily, standing firm on his argument. Sartre then joined in, claiming that Camus’s rejection of revolution was nothing less than a rejection of responsibility itself.

The dispute exploded beyond the journal. Newspapers across France covered it, and the feud turned into a cultural event. The Camus and Sartre relationship, once seen as a symbol of unity, has now become a symbol of division. The public followed the quarrel as if it were a political trial.

The deeper issue was clear. The Camus vs Sartre freedom debate centered on the price of justice. Sartre accepted violence as a temporary necessity; Camus saw it as a betrayal. Their break showed that ideas could divide as bitterly as politics themselves. The friendship had ended, but the questions it raised, about freedom, justice, and responsibility, remained alive in postwar Europe.

RELATED READING: Absurdism vs. Nihilism vs. Existentialism: Meaning, Differences, And Examples

Lessons From The Camus–Sartre Feud On Freedom

What survives from the Camus–Sartre dispute is not gossip but an argument about freedom that still matters. Both men agreed that philosophy must address life after catastrophe. They disagreed about the cost of justice.

Camus believed how to be free meant living within limits. His revolt was never against humanity itself. He thought violence deformed liberty and turned ideals into excuses. Sartre believed liberty was worthless without equality. For him, injustice left no neutral ground. If violence were required to secure justice, then it could be defended.

The Camus vs Sartre political philosophy debate endures because both positions hold truth. Freedom without justice protects only the privileged. Justice without freedom can collapse into tyranny. This tension remains at the heart of modern politics.

The lesson is clear enough, but never easy. How to be free is a question that Camus and Sartre answered in opposite ways, yet both still resonate. For Camus, absolutism was the enemy of liberty. For Sartre, complacency meant injustice would remain. The Camus vs Sartre political philosophy debate endures because it demands that we face a constant question: which threat is greater, and what cost of freedom or justice are we willing to pay?

Choosing Between Two Visions Of Freedom

To understand why the Camus vs Sartre dispute still attracts attention, one must see how closely it speaks to today. Camus warned that freedom cannot survive when politics embraces absolutes. In an age where authoritarianism threatens, his caution sounds timely. Sartre argued that freedom is impossible without equality. At a moment of widening social divides, his urgency feels equally valid.

The Camus vs Sartre freedom dilemma is not abstract. It poses real questions that societies must answer. Which danger is greater: too much restraint, or too much upheaval? Can justice be delayed without denying liberty? Can freedom survive when inequality defines opportunity?

Camus’s appeal was to moderation, Sartre’s to revolution. Each distrusted what the other defended. Yet their arguments remain inseparable, because the problem they described is permanent. Freedom and justice do not align perfectly; they strain against one another.

It underlines that the dispute was less about closing arguments than about keeping the questions alive. To read Camus and Sartre together is to recognize that freedom’s meaning is always unfinished, always shaped by the conflicts of its time.

Conclusion: Freedom’s Divided Legacy

The friendship that once united Camus and Sartre ended in sharp division. Yet the arc of the Camus vs Sartre relationship is less about personalities than about philosophy in action. Their partnership symbolized Europe’s search for meaning after war; their quarrel symbolized its struggle to define justice.

Camus’s answer to how to be free placed dignity and restraint at the center. He refused to allow ideals to excuse violence. Sartre tied justice to collective struggle and accepted that revolution might be part of it. Neither he nor Camus gave up on freedom, yet each gave it a different shape, and in that difference their teaching still endures. Camus said freedom without limits risks tyranny. Sartre said freedom without equality slides into privilege.

Read together, they show that liberty and justice depend on each other, though the union will always remain incomplete.

Their quarrel endures because it keeps the questions alive. What is the cost of justice? What is the cost of freedom? Each generation must answer again, knowing that the balance is never final. Camus and Sartre did not reconcile, but their dispute still teaches us that philosophy matters when it refuses to let us rest easy.

9 Books On Asexuality That Shatter All The Myths And Misconceptions

Romance And Ruin: Ranking The Most Toxic Couples In Shakespeare’s Plays